Data Structures and Sequences

Tuple

A tuple is fixed-length, immutable sequence of Python objects. The easiest way to create one is with a comma-separated sequence of values

1

2

3

tup = 4,5,6

tup

Output: (4, 5, 6)

When you’re defining tuples in more complicated expressions, it’s often necessary to enclose the values in parentheses, as in this example of creating a tuple of tuples:

1

2

3

nested_tup = (4,5,6), (7,8)

nested_tup

Output: ((4, 5, 6), (7, 8))

To convert any sequence or iterator to a tuple, we use the tuple function

1

2

tuple([4,0,2])

Output:(4, 0, 2)

Elements in a tuple can be accessed with square brackets [] as with most other sequence types.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

tup

Output: (4, 5, 6)

tup[0]

Output: 4

tup[2]

Output: 6

While the objects stores in a tuple may be mutable themselves, once the tuple is created it’s not possible to modify which object is stored in each slot

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

tup = tuple(['foo', [1,2], True])

tup[2] = False

Output:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-13-b89d0c4ae599> in <module>()

----> 1 tup[2] = False

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

If an object inside a tuple is mutable, such as lists, you can modify it in-place

1

2

3

4

5

6

tup[1].append(3)

tup

Output: ('foo', [1, 2, 3], True)

We can concatenate tuples using the + operator to produce longer tuples

1

2

3

(4, None, 'foo') + (6,0) + ('bar',)

Output: (4, None, 'foo', 6, 0, 'bar')

Multiplying a tuple by an integer, as with lists, has the effect of concatenating together that many copies of the tuple

1

2

3

('foo', 'bar') * 4

Output: ('foo', 'bar', 'foo', 'bar', 'foo', 'bar', 'foo', 'bar')

Unpacking Tuples

If we try to assign a tuple-like expressino of variables, Python will attempt to unpack the value on the righthand side of the equals sing:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

tup = (4,5,6)

a, b, c = tup

a

Output: 4

b

Output: 5

c

Output: 6

Even sequences with nested tuples can be unpacked

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

tup = 4,5,(6,7)

a,b,(c,d) = tup

a

Output: 4

b

Output: 5

c

Output: 6

d

Output: 7

In python swap can be done like this

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

a, b = 1,2

a

Output: 1

b

Output: 2

a, b = b, a

a

Output: 2

b

Output: 1

A common use of variable unpacking is iterating over sequences of tuples or lists

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

seq = [(1,2,3), (4,5,6), (7,8,9)]

for a,b,c, in seq:

print(f"a: {a}, b: {b} & c: {c}")

Output:

a: 1, b: 2 & c: 3

a: 4, b: 5 & c: 6

a: 7, b: 8 & c: 9

Another common use is returning multiple values form a function.

The python language recently acquired some more advanced tuple unpacking to help with situations where you may want to pluck a few elements from the beginning of a tuple. This uses the special syntax *rest, which is also used in function signatures to capture an arbitrarily long list of positional arguements

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

values = 1,2,3,4,5

a, b, *rest = values

a

Output: 1

b

Output: 2

rest

Output: [3, 4, 5]

It is conventional among python programmers to use underscore (_) for unwanted variables instead of rest

1

2

3

a, b, *_ = values

_

Output: [3, 4, 5]

Tuple Methods

Since the size and contents of a tuple cannot be modified, it is very light on instance methods. A particularly useful one is count which counts the number of occurences of a value.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

a = (1,2,2,2,3,4,2)

a.count(1)

Output: 1

a.count(2)

Output: 4

a.index(4)

Output: 5

a.index(2)

Output: 1

Here, the index method in a tuple only returns the index of the first match object if the values are repeated.

List

In contrast to tuples, lists are variable length and their contents can be modified in-place. We can define them using square brackets [] or using the list type function

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

a_list = [2,3,7, None]

tup = ('foo', 'bar', 'baz')

b_list = list(tup)

b_list

Output: ['foo', 'bar', 'baz']

b_list[1] = 'peekaboo'

b_list

Output: ['foo', 'peekaboo', 'baz']

The list function is frequently used in data processing as a way to materialize an interator or generator expression.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

gen = range(10)

gen

Output: range(0, 10)

list(gen)

Ouptut: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Adding and Removing Elements

Elements can be appended to the end of the list with the append method

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

b_list

Output: ['foo', 'peekaboo', 'baz']

b_list.append('dwarf')

b_list

Output: ['foo', 'peekaboo', 'baz', 'dwarf']

Using insert an element can be inserted at a specific location in the list

1

2

3

4

b_list.insert(1, 'red')

b_list

Output: ['foo', 'red', 'peekaboo', 'baz', 'dwarf']

Note: The insertion index must be between 0 and the length of the list, inclusive

The inverse operation to insert is pop, which removes and returns an element at a particular index

1

2

3

4

5

b_list.pop(2)

Output: 'peekaboo'

b_list

Output: ['foo', 'red', 'baz', 'dwarf']

If the index is non provided to the pop function then the last element in the list will be removed

1

2

3

4

5

b_list.pop()

Output: 'dwarf'

b_list

Output: ['foo', 'red', 'baz']

Elements can also be removed by value with remove, which locates the first such value and removes it from the list

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

b_list.append('foo')

b_list

Output: ['foo', 'red', 'baz', 'foo']

b_list.remove('foo')

b_list

Output: ['red', 'baz', 'foo']

To check if a list contains a value, we use the in keyword.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

'dwarf' in b_list

Output: False

'red' in b_list

Output: True

'dwarf' not in b_list

Output: True

Checking whether a list contains a value is a lot slower than doing so with dicts and sets, as Python makes a linear scan across the values of the list, whereas it can check the others in constant time.

Concatenating and combining lists

Similar to tuples, adding two lists together with + concatenates them

1

2

[4, None, 'foo'] + [7,8,(2,3)]

Output: [4, None, 'foo', 7, 8, (2, 3)]

If we have a list already defined, we can append multiple elements or another lists ot it using the extend method

1

2

3

4

5

6

x = [4, None, 'foo']

x.extend([7,8,(2,3)])

x

Output: [4, None, 'foo', 7, 8, (2, 3)]

Note: List concatenation by addition is comparatively expensive operation since a new list must be created and the objects coped over. Using extend to append elements to an existing list, especially if we are building up a large list, is usually preferable

Sorting

We can sort a list in-place by calling its sort function

1

2

3

4

a = [7,2,5,1,3]

a.sort()

a

Output: [1, 2, 3, 5, 7]

sort has a few options that will occasionally come in handy. One is the ability to pass a secondary sort key-that is, a function that produces a value to use to sort the objects

1

2

3

4

b = ['saw', 'small', 'he', 'foxed', 'six']

b.sort(key=len)

b

Output: ['he', 'saw', 'six', 'small', 'foxed']

Binary Search and maintaining a sorted list

The built-in bisect module implements binary search and insertion into a sorted list. bisect.bisect finds the location where an element should be inserted to keep it sorted, while bisect.insort actually inserts the element into that location

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

import bisect

c = [1,2,2,2,3,4,7]

bisect.bisect(c,2)

Output: 4

bisect.bisect(c,5)

Output: 6

bisect.insort(c,6)

c

Output: [1, 2, 2, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7]

Note: The bisect module functions do not check whether the list is sorted, as doing so would be computataionally expensive. Thus, using them with an unsorted list will succeed without erorr but may lead to incorrect results.

Slicing

We can select sections of most sequence types by using slice notatoin, which in its basic form consits of start:stop(exclusive) passed to thte indexing operator[]:

1

2

3

4

5

6

seq = [7,2,3,7,5,6,0,1]

len(seq)

Output:8

seq[1:5]

Output:[2, 3, 7, 5]

Slices can also be assigned to with a sequence

1

2

3

4

5

6

seq[3:4]= [6,3]

seq

Output:[7, 2, 3, 6, 3, 5, 6, 0, 1]

len(seq)

Output:9

While the element at the start index is included, the stop index is not included, so that the number of elements in the result is stop - start

Either the start or stop can be omitted, in which case they default to the start of the sequence and the end of the sequence, respectively

1

2

seq[:5]

Output: [7, 2, 3, 6, 3]

Negative indices slice the sequence relative to the end:

1

2

3

4

5

seq[-4:]

Output:[5, 6, 0, 1]

seq[-6:-2]

Output:[6, 3, 5, 6]

A step can be used after a second colon to say, take every other element

1

2

3

4

5

seq

Output:[7, 2, 3, 6, 3, 5, 6, 0, 1]

seq[::2]

Output: [7, 3, 3, 6, 1]

A clever use of this is to pass -1, which has the useful effect of reversing a list or tuple

1

2

seq[::-1]

Output:[1, 0, 6, 5, 3, 6, 3, 2, 7]

Built-in Sequence Functions

enumerate - It’s common when interating over a sequence to want to keep track of the index of the current item. The enumerate is a built in python function, which returns a sequnece of (index, value) tuples

Syntax:

1

2

3

4

i = 0

for i, value in enumerate(collection):

# do something with value

i+=1

When we are indexing data, a helpful pattern that uses enumerate is computing a dict mapping the values of a sequence(which are assumed to be unique) to their locations in the sequence

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

some_list = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz']

mapping = {}

for index, value in enumerate(some_list):

mapping[index] = value

mapping

Output: {0: 'foo', 1: 'bar', 2: 'baz'}

sorted - The sorted function returns a new sorted list from the elements of any sequence

1

2

sorted([7,1,2,6,0,3,2])

Output: [0, 1, 2, 2, 3, 6, 7]

The sorted function acccepts the same arguements as the sort method on lists

1

2

3

words = ['the', 'sorted', 'function', 'accepts', 'the', 'same']

sorted(words,key = len)

Ouput:['the', 'the', 'same', 'sorted', 'accepts', 'function']

zip - It pairs up the elements of a number of lists, tuples or other sequences to create a list of tuples

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

seq1 = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz']

seq2 = ['one', 'two', 'three']

zipped = zip(seq1, seq2)

zipped

Output: <zip at 0x1cba23b5f88>

list(zipped)

Output:[('foo', 'one'), ('bar', 'two'), ('baz', 'three')]

zipcan take an arbitrary number of sequences, and the number of elements it produces is determined by the shortest sequence:

1

2

3

seq3 = ['False', 'True']

list(zip(seq1, seq2, seq3))

Output: [('foo', 'one', 'False'), ('bar', 'two', 'True')]

A very common use of zip is simultaneously iterating over multiple sequences, possibly also combined with enumerate

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

seq1

Output:['foo', 'bar', 'baz']

seq2

Output:['one', 'two', 'three']

for i, (a,b) in enumerate(zip(seq1, seq2)):

print(f"{i}: {a}, {b}")

Output:

0: foo, one

1: bar, two

2: baz, three

Given a zipped sequence, zip can be applied in a clever way to unzip the sequence. Another way to think about this converting a list of rows into a list of columns.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

pitchers = [('Nolan', 'Ryan'), ('Roger', 'Clemens'),

('Schilling', 'Curt')]

first_name, last_name = zip(*pitchers)

first_name

Output: ('Nolan', 'Roger', 'Schilling')

last_name

Output: ('Ryan', 'Clemens', 'Curt')

reversed - reversed iterates over the elements of a sequence in reverse order

1

2

list(reversed(range(10)))

Output:[9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0]

dict

dict is likely the most important built-in python data structure. A more common name for it is hash map or associative array. It is a flexibly sized collection of key-value pairs, where key and value are Python objects. One approach to creating one is to use curly braces {} and colons to seperate keys and values.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

empty_dict = {}

d1 = {'a': 'some value', 'b':[1,2,3,4]}

d1

Output:

{

'a': 'some value',

'b': [1, 2, 3, 4]

}

We can access, insert or set elements using the same sytanx as for accesing elements of a list or tuple

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

d1[7] = 'an integer'

d1

Output:

{

'a': 'some value',

'b': [1, 2, 3, 4],

7: 'an integer'

}

d1['b']

Output:[1, 2, 3, 4]

We can check if a dict contains a key using the same syntax used for checking whether a list or tuple contains a value

1

2

3

4

5

'b' in d1

Output: True

'b' in d1.keys()

Output:True

We can delete the values either using the del keyword or the pop method(which simultaneously returns the value and deletes the key)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

d1[5] = 'some value'

d1

Output:

{

'a': 'some value',

'b': [1, 2, 3, 4],

7: 'an integer',

5: 'some value'

}

d1['dummy'] = 'another value'

d1

Output:

{

'a': 'some value',

'b': [1, 2, 3, 4],

7: 'an integer',

5: 'some value',

'dummy': 'another value'

}

del d1[5]

d1

Output:

{

'a': 'some value',

'b': [1, 2, 3, 4],

7: 'an integer',

'dummy': 'another value'

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

ret = d1.pop('dummy')

ret

Output:'another value'

d1

Output:

{

'a': 'some value',

'b': [1, 2, 3, 4],

7: 'an integer'

}

The keys and values method give you iterators of the dict’s keys and values, respectively. While the key-value pairs are not in any particular order, these functions output the keys and values in the same order

1

2

3

4

5

list(d1.keys())

Output: ['a', 'b', 7]

list(d1.values())

Output:['some value', [1, 2, 3, 4], 'an integer']

We can merge one dict into another using the update method

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

d1.update({'b' : 'foo', 'c': 12})

d1

Output:

{

'a': 'some value',

'b': 'foo',

7: 'an integer',

'c': 12

}

The update methods changes dicst in-place, so any existing keys in the data passed to the update will have their old values discarded

Creating dicts from sequences

It is common to occasionally end up with two sequences that you want to pair up element-wise in a dict.

1

2

3

mapping = {}

for key, value in zip(key_list, value_list):

mapping[key]= value

Since a dict is essentially a collection of 2 tuples, the dict function accepts a list of 2-tuples

1

2

3

4

mapping = dict(zip(range(5), reversed(range(5))))

mapping

Output:{0: 4, 1: 3, 2: 2, 3: 1, 4: 0}

Default Values

1

2

3

4

5

6

It is very common to have logic like:

if key in some_dct:

value = some_dict[key]

else:

value = default_value

Thus, the dict methods get and pop can take default value to be returned, so that the above if-else block can be written as simply as:

1

value = some_dict.get(key,default_value)

get by default will return None if they key is not present, while pop will raise an exception

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

words = ['apple', 'bat', 'bat', 'atom', 'book']

by_letter= {}

for word in words:

letter = word[0]

if letter not in by_letter:

by_letter[letter] = [word]

else:

by_letter[letter].append(word)

by_letter

Output:{'a': ['apple', 'atom'], 'b': ['bat', 'bar', 'book']}

The setdefault dict method is for precisely this purpose. The preceding for loop can be rewritten as:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

for word in words:

letter = word[0]

by_letter.setdefault(letter,[]).append(word)

by_letter

Output:

{

'a': ['apple', 'atom'],

'b': ['bat', 'bar', 'book']

}

The built-in collections module has a useful class, defaultdict, which makes this even easier. TO create one, you pass a type or function for generating the default valu for each slot in the dict:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

from collections import defaultdict

by_letter = defaultdict(list)

for word in words:

by_letter[word[0]].append(word)

by_letter

Output: defaultdict(list, {'a': ['apple', 'atom'], 'b': ['bat', 'bar', 'book']})

Valid dict key types

While the values of a dict can be any Python object, the keys generally have to be immutable objcets like scalar types(int, float, string) or tuples(all the objects in the tuple need to be immutable, too). The technical term here is hashabiility. We can check whether an object is hashable(cann be used as a key in dict) with the hash function

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

hash('string')

Output: -8095158123584499513

hash((1,2,(2,3)))

Output: 1097636502276347782

hash((1,2,[2,3]))

Output:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-190-576218ff90d3> in <module>()

----> 1 hash((1,2,[2,3]))

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

To use list as a key, one option is to convert it to a tuple, which can be hashes as long as its elements also can:

1

2

3

4

d = {}

d[tuple([1,2,3])] = 5

d

Output: {(1, 2, 3): 5}

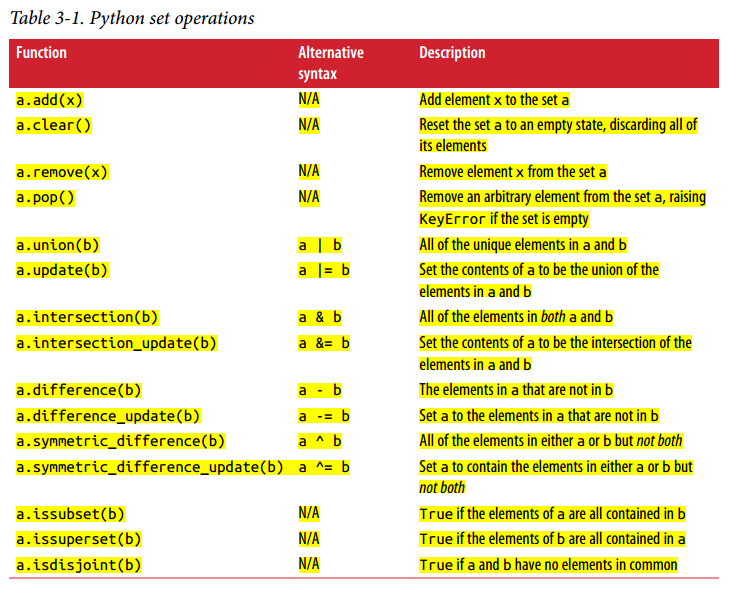

Set

A set is an unordered collection of unique elements. We can think of them like dicts, buy keys only, no values. A set can be created in two ways: via the set function or via a set literal with curly braces

1

2

3

4

5

set([2,2,2,1,3,3])

Output: {1, 2, 3}

{2,2,2,1,3,3,}

Output:{1, 2, 3}

Sets support mathematical set operations like union, intersection, difference, and symmetric difference.

1

2

a = {1,2,3,4,5}

b = {3,4,5,6,7,8}

The union of these two sets is the set of distinct elements occuring in etiher set. This can be computed with either the unioni method or the | binary operator.

1

2

3

4

5

a.union(b)

Output {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

a | b

Output: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

The intersection contains the elements occuring in both sets. The & operator or the intersection method can be used.

1

2

3

4

5

a.intersection(b)

Output: {3, 4, 5}

a & b

Output: {3, 4, 5}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

a

Output: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

c = a.copy()

c

Output: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

c|= b

c

Output: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

d = a.copy()

d

Output: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

d&=b

d

Output: {3, 4, 5}

Like dicts, set elements generally must be immutable. To have list-like elemetns you must convert it to a tuple:

1

2

3

4

5

my_data = [1,2,3,4]

my_set= {tuple(my_data)}

my_set

Output: {(1, 2, 3, 4)}

We can also check if a set is a subset of (is contained in) or a superset of (contains all elements of) another set

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

a_set = {1,2,3,4,5}

{1,2,3}.issubset(a_set)

Output:True

a_set.issuperset({1,2,3})

Output:True

Sets are equal if and only if their contents are equal:

1

2

{1,2,3} == {3,2,1}

Output: True

List, Set and Dict Comprehensions

List comprehension allows us to concisely from a new list by filtering the elements of a collection, transforming the elements passing the filter in one concide expression of the form:

Syntax:

This is equivalent to the following for loop:

1

2

3

4

result = []

for val in collection:

if condition:

result.append(expr)

1

2

3

4

strings = ['a', 'as', 'bat', 'car', 'dove', 'python']

[x.upper() for x in strings if len(x) > 2]

Output: ['BAT', 'CAR', 'DOVE', 'PYTHON']

Set and dict comprehensions are a natural extension, producing sets and dicts in an idiomatically similar way instead of lists. A dict comprehension looks like this:

1

dict_comp = {key-expr: value-expr for value in collection if condition

A set comprehension looks like the equivalent list comprehension except with curly braces instead of square brackets:

1

set_comp = {expr for value in collection if condition}

1

2

3

4

5

6

strings

Output: ['a', 'as', 'bat', 'car', 'dove', 'python']

unique_lengths = {len(x) for x in strings}

unique_lengths

Output: {1, 2, 3, 4, 6}

We could also express this more functionally using the map function

1

2

set(map(len, strings))

Output: {1, 2, 3, 4, 6}

As a simple dict comprehesion example, we could create a lookup map of these strings to their locations in the list:

1

2

3

loc_mapping = {value: index for index, value in enumerate(strings)}

loc_mapping

Output: {'a': 0, 'as': 1, 'bat': 2, 'car': 3, 'dove': 4, 'python': 5}

Nested List Comprehensions

1

2

all_data = [['John', 'Emily', 'Micheal', 'Mary', 'Steven'],

['Maria', 'Juan', 'Javier', 'Natalia', 'Pillar']]

To get a single list containing all names with two or more e’s in them we could do this with a simple for loop:

1

2

3

4

5

6

names_of_interest = []

for names in all_data:

enough_es = [name for name in names if name.count('e')>=2]

names_of_interest.extend(enough_es)

names_of_interest

Output: ['Steven']

But we can actually wrap this whole operation up in a single nested list comprehension like:

1

2

3

result = [name for names in all_data for name in names if name.count('e')>=2]

result

Output: ['Steven']

At first, nested list comprehensions are a bit hard to wrap your head around. The for parts of the list comprehension are arranged according to the order of nesting, and any filter condition is pull at the end as before. Here is another example where we ‘flatten’ a list of tuple of integers into a simple list of integers

1

2

3

4

some_tuples = [(1,2,3),(4,5,6),(7,8,9)]

flattened = [x for tup in some_tuples for x in tup]

flattened

Output: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Kepp in mind that the order of the for expression would be the same if we wrote a nested for loop instead of a list comprehension:

1

2

3

4

flattened = []

for tup in some_tuples:

for x in tup:

flattened.append(x)

Building a list of lists using list comprehension

1

2

[[x for x in tup]for tup in some_tuples]

Output: [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

Functions

1

2

3

4

5

def my_function(x,y, z= 1.5):

if z > 1:

return z * (x+y)

else:

return z/ (x + y)

There is no issue with multiple return statements. If Python reaches the end of a function without encountering a return statemetn, None is returned automatically.

Each function can have positional arugments and keyword arguements. Keyword arguements are most commonly used to speccify default values or optional arguements. In the preceding fucntion, x and y are positional arguements while z is a keyword arguments. This means that the function can be called in any of these ways:

1

2

3

my_function(5,6,z=0.7)

my_function(3.14,7,3.5)

my_function(10,20

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

my_function(5,6,z=0.7)

Output: 0.06363636363636363

my_function(3.14,7,3.5)

Output: 35.49

my_function(10,20)

Output: 45.0

The main restriction on function arguments is that the keyword arguments must always follows the positional arguements (if any).

Namespaces, Scope and Local Functions

Functions can access variables in two different scopes: global and local. An alternative and more descriptive name describing a variable scope in Python is a namespace. Any variables that are assigned within a function by default are assigned to the local namespace. The local namespace is created when the function is called and immedi‐ ately populated by the function’s arguments. After the function is finished, the local namespace is destroyed (with some exceptions that are outside the purview of this chapter).

1

2

3

4

def func():

z = []

for i in range(5):

z.append(i)

When func() is called, the empty list z is created, five elements are appended, and then z is destroyed when the function exits.

Suppose instead we had declared z as follows:

1

2

3

4

z = []

def func():

for i in range(5):

z.append(i)

Assigning variables outside of the function’s scope is possible, but those variables must be declared as global via the global keyword

1

2

3

4

5

a = None

def bind_a_variable():

global a

a = []

1

2

3

4

5

bind_a_variable

Output: <function __main__.bind_a_variable>

print(a)

Output: None

Returning Multiple Values

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

def f():

a = 5

b = 6

c = 7

return a,b,c

a,b,c, = f()

a

Output: 5

b

Output: 6

c

Output: 7

A potentially attractive alternative to returning multiple values like before might be to return a dict instead

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

def f():

a = 5

b = 6

c = 7

return {'a': a, 'b': b, 'c': c}

f()

Output: {'a': 5, 'b': 6, 'c': 7}

Functions Are Objects

Since Python functions are objects, many constructs can be easily expressed that are difficult to do in other languages.

1

states = [' Alababa', 'Georgiga!', 'Georgia', 'georgia', 'FlOrIda', 'south carolina##', 'West virginia?']

To convert it into standard data we have to strip whitespace, remove puncutation symbols and standardize on propercapitalizaiton. One way to do this is to use built-in string methods along with the ‘re’ standarad library module for regular expressions

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

import re

def clean_strings(strings):

result = []

for value in strings:

value = value.strip()

value = re.sub('[!#?]', '', value)

value = value.title()

result.append(value)

return result

clean_strings(states)

Output: ['Alababa',

'Georgiga',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Florida',

'South Carolina',

'West Virginia']

An alternative approach that we may find useful is to make a list of the operations we want to apply to a particular set of strings

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

def remove_punctuation(value):

return re.sub('[!#?]', '', value)

clean_ops = [str.strip, remove_punctuation, str.title]

def clean_strings(strings, ops):

result = []

for value in strings:

for function in ops:

value = function(value)

result.append(value)

return result

clean_strings(states, clean_ops)

Output: ['Alababa',

'Georgiga',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Florida',

'South Carolina',

'West Virginia']

A more functional pattern like this enables you to easily modify how the strings are transformed at a very high level. The clean_strings function is also now more reus‐ able and generic|

Anonymous or Lambda Functions

Python has a support for so-called anonymous or lambda functions, which are way of writing functions consisting of a single statment, the result of which is the return value. They are defined with the lambda keyword, which has no meaning other than “we are declarign an anonymous function”

1

2

def short_function(x):

return x * 2

1

equivalent_anonymous = lambda x : x * 2

Lambda functions are especially convenient in data analysis because, there are many cases where data transformation functions will take functions as arguments. It is often less typing (and clearer) to pass a lambda function as opposed to writing a full-out function declaration or even assigning the lambda function to a local variable.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def apply_to_list(some_list, f):

return [f(x) for x in some_list]

ints = [4,0,1,5,6]

apply_to_list(ints, lambda x : x * 2)

Output: [8, 0, 2, 10, 12]

strings = ['foo', 'card', 'bar', 'aaaa', 'abab']

strings.sort(key = lambda x: len(set(list(x))))

strings

Output:['aaaa', 'foo', 'abab', 'bar', 'card']

Note: One reason lambda functions are called anonymous functions is that, unlike functions declared with the def keyword, the function object itself is never given an explicit name attribute

Currying: Partial Argument Applicatoin

Currying is computer science jargon that means deriving new functions from existing ones by partial argument application.

1

2

3

4

def add_numbers(x,y):

return x + y

add_numbers(3,4)

Output:7

Using this function, we could derive a new function of one varibale, add_five, that adds 5 to its arguements

1

2

3

add_five = lambda y: add_numbers(5,y)

add_five(6)

Output: 11

Here, the second argument to add_numbers is said to be curried.

The built-in functools module can simplify this process using the partial function

1

2

3

4

5

from functools import partial

add_five = partial(add_numbers,5)

add_five(4)

Output: 9

Generators

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

some_dict = {'a': 1, 'b': 2, 'c': 3}

for key in some_dict:

print(key)

Output:

a

b

c

1

2

3

dict_iterator = iter(some_dict)

dict_iterator

Output: <dict_keyiterator at 0x1fa490413b8>

An iterator is any object that will yeild objects to the Python interpreter when used in a context like a for loop

1

2

list(dict_iterator)

Output: ['a', 'b', 'c']

itertools module

The standard library itertools module has a collection of generators for many common data algorithms. For example, groupby takes any sequence and a function, grouping consecutive elements in the sequence by return value of the function. Here’s an example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

import itertools

first_letter = lambda x: x[0]

names = ['Alan', 'Adam', 'Wes', 'Will', 'Albert', 'Steven']

for letter, names in itertools.groupby(names, first_letter):

print(f"Letter : {letter} - {list(names)}")

Output:

Letter : A - ['Alan', 'Adam']

Letter : W - ['Wes', 'Will']

Letter : A - ['Albert']

Letter : S - ['Steven']

Errors and Exception Handling

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

float('1.2345')

Output: 1.2345

float('something')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-55-2649e4ade0e6> in <module>()

----> 1 float('something')

ValueError: could not convert string to float: 'something'

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except Exception as exc:

return f"Excpetions occured as: {exc}"

attempt_float('1.2345')

Output:1.2345

1

2

attempt_float('something')

Output: "Excpetions occured as: could not convert string to float: 'something'"

We might want to suppress ValueError, since a TypeError might indicate a legitimate bug in your program. To do that, write the exception type after except:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except ValueError:

return x

attempt_float((1,2))

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-60-102527222085> in <module>()

----> 1 attempt_float((1,2))

<ipython-input-59-6209ddecd2b5> in attempt_float(x)

1 def attempt_float(x):

2 try:

----> 3 return float(x)

4 except ValueError:

5 return x

TypeError: float() argument must be a string or a number, not 'tuple'

We can catch multiple exception types by writing a tuple of exception types intead

1

2

3

4

5

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except (TypeError, ValueError):

return x

In some cases, we may not want to suppress an exception, but you want some code to be executed regardless of whether the code in the try block succees or not, To do this, we use finally:

1

2

3

4

5

6

f = open(path, 'w')

try:

write_to_file(f)

finally:

f.close()

Here, the file handle f will always get closed. Similarly, you can have code that executes only if the try: block succeeds using else:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

f = open(path, 'w')

try:

write_to_file(f)

except:

print('Failed')

else::

print('Succeeded')

finally:

f.close()